news

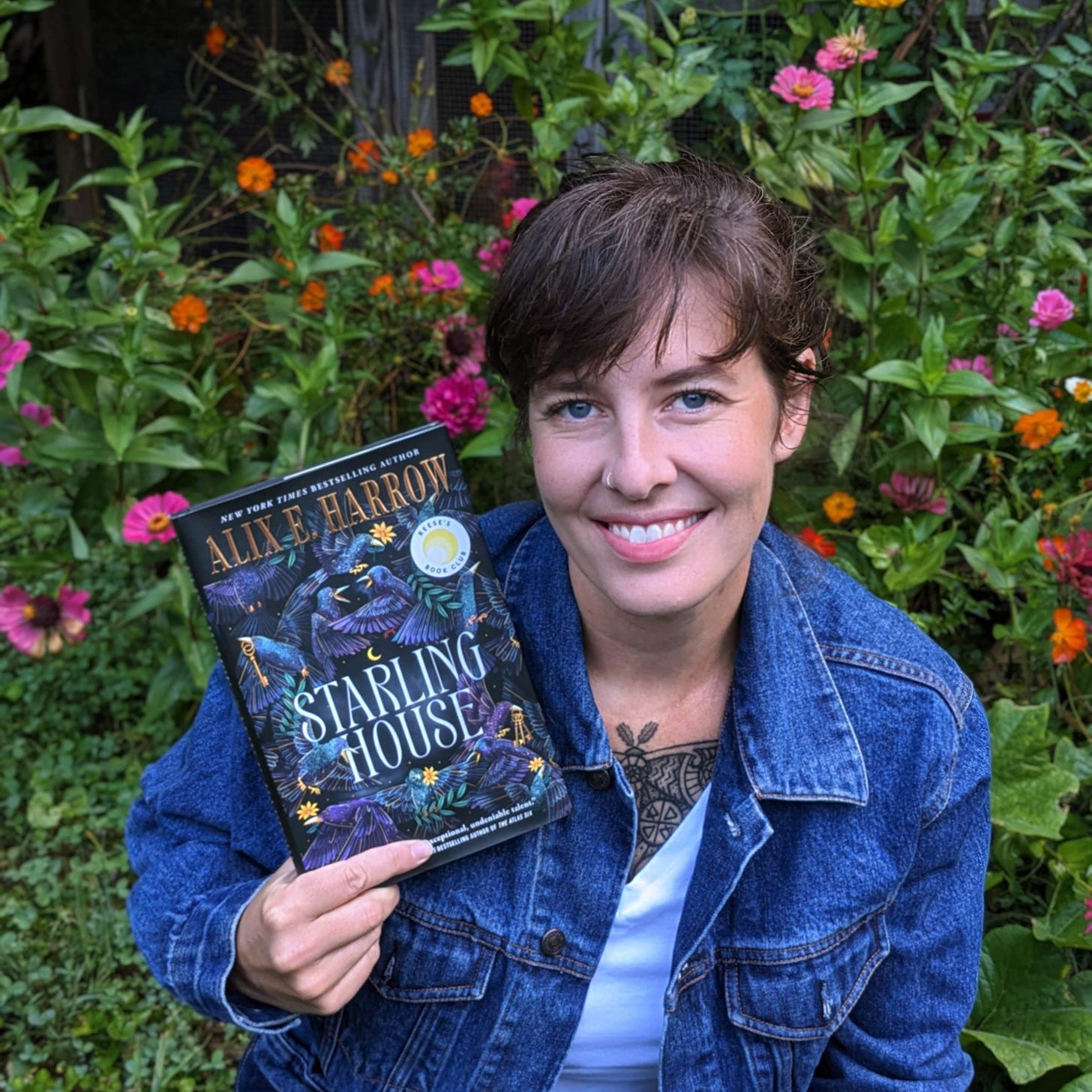

starling house—my third novel—is out now. it’s sort of a southern gothic beauty and the beast, and you can find it wherever books are sold.1

signed copies and other editions: you can order signed copies through my local indie store, new dominion bookshop, or from any of the shops on my tour list (below). barnes & noble also has an exclusive edition, with fancy endpapers, a case stamp, and a bonus epilogue. no matter what edition you buy, there are five full-page illustrations from rovina cai—one of my favorite living artists. the audiobook is read by the award-winning natalie naudus.

flowers, etc: it received some starred reviews and some very lovely blurbs from some very lovely people. it was on lots of lists and the cover of the october issue of bookpage. it’s an indie next pick, a libraryreads pick, a libro.fm bookseller pick, the october pick for book of the month, an amazon best SFF book of the month, and the Illumicrate book for november.

it is also—and this is the kind of news that makes your editor call you on the phone like in a movie—the Reese’s Book Club pick for october. yes, that reese. i wasn’t allowed to tell anyone for months, and as a result i don’t have any practice in delivering this news in a likeable manner (grateful, awed, chill but not too chill, humble but not too humble, aware of my privilege but not to the point of making it weird for anyone). i can only be what i am: in shock, and unsure of how to hold my arms.

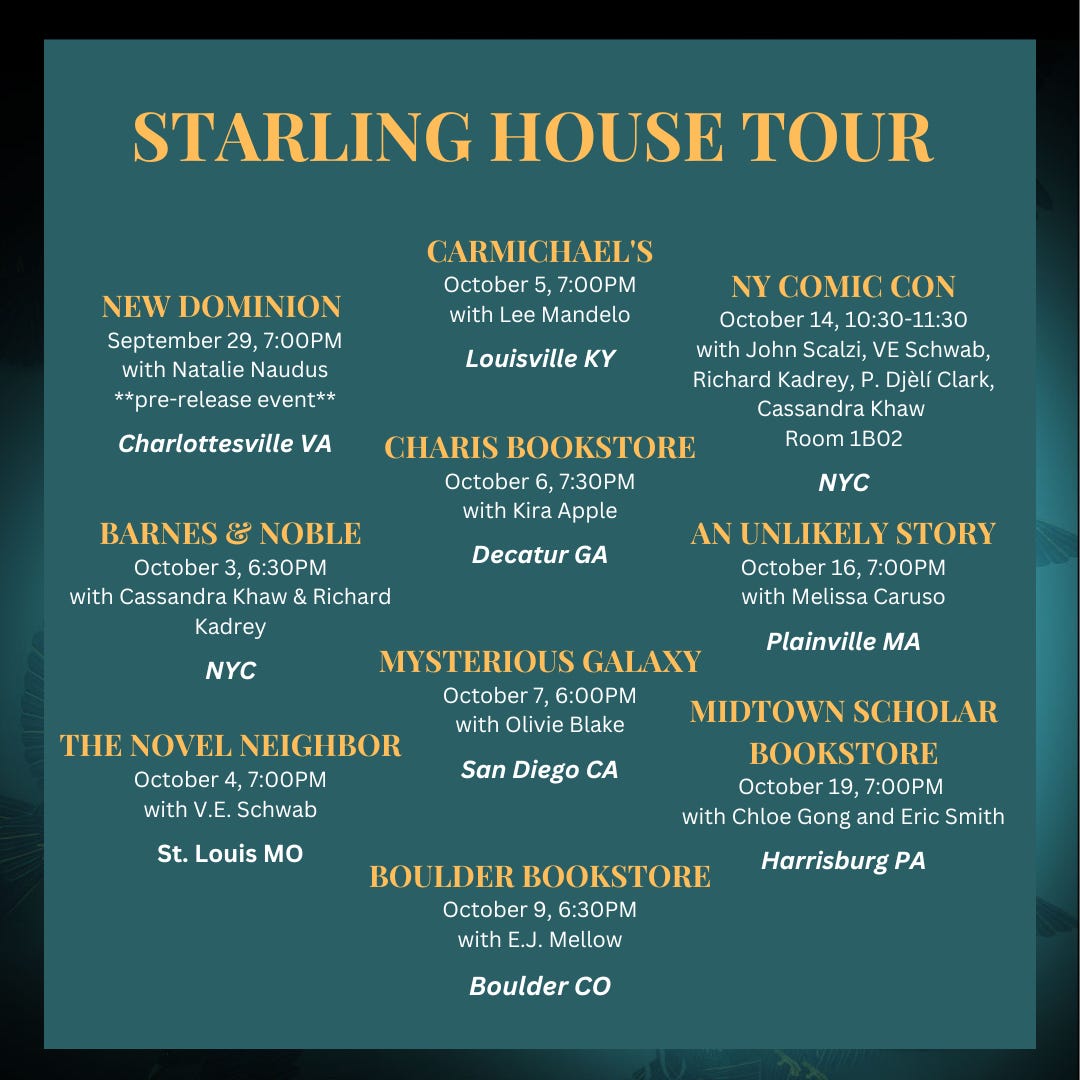

events: and now…i’m on tour! you can come see me tonight talking with cass khaw and richard kadrey about their gristly, grisly, gruesome, funny, weirdly sweet horror novel, The Dead Take the A Train, at Barnes & Noble Tribeca in NYC. the rest of my tour stops are listed here.

none of this would have happened without the hard work, organization, time, talent, and patience of tor’s publishing team. giselle, isa, sarah, tessa, emily, rachel, khadija, miriam—i hope you’re doing better things with your spare time than reading my newsletter, but thank you. my agent, kate mckean, is the only reason i get to work with these people, and my husband, nick, is the only reason the books get written in the first place.

the history of starling house

so, starling house is set in muhlenberg county, kentucky, in a town called eden, which doesn’t exist.2 eden is based on a town called paradise, which also doesn’t exist—although it used to.

if you drove through paradise today, you wouldn’t see anything but the carcass of a power plant, now abandoned, and an old cemetery.

the story of paradise changes according to who you ask, and who’s doing the asking. the version you might hear in muhlenberg county goes like this:

once there was a little town built on the banks of the green river, where the land was so rich and lovely that the first settlers named it paradise. they were simple, hardworking folk, who made an honest living shipping tobacco upriver--not knowing they were sitting on top of a fortune in anthracite. in 1962, peabody coal built the biggest steam shovel in the world and made muhlenberg county the number one coal producer in the country. most of that coal went straight to the paradise steam plant, the largest coal-fired power plant ever built, which employed more than a thousand people and sent power all the way to nashville.

when the coal finally ran dry a couple of decades later, the steam shovel dug its own grave. it got a hero’s funeral, with state officials and press photographers in attendance.

this is a story of progress and profit, an ode to post-WWII american industry and ingenuity. it feels like it should be delivered in an old-timey news voice—which it often was. it’s a story of greatness, of excess—everything is the biggest, the most, the highest. when he was a kid, my dad got to take the elevator to the top of peabody’s steam shovel--twenty stories straight up!--because they were so proud of their machine that they offered rides.

of course, there’s another version of this story. you might already know it—i sort of thought everybody did, but by now i’ve seen enough politely blank faces on this tour to recognize that john prine is not, perhaps, the household name i thought he was.

anyway, “paradise” was one of his first hits, recorded in 1971. the chorus goes like this:

Daddy won't you take me back to Muhlenberg County

Down by the Green River where Paradise lay.

Well, I'm sorry my son, but you're too late in asking

Mister Peabody's coal train has hauled it away.

prine’s version starts just like the other one: with a little town on the banks of the green river. idyllic, innocent, perfect—edenic, even. but here, mr. peabody is the villain. which, of course, he was: his steam shovel strip-mined more than fifty thousand acres of western kentucky. the green river turned brown. people complained that their chests hurt and their eyes stung. they said if you hung white laundry on the line, it would be gray by the time it was dry. they began to leave.

by 1967, the tva was forced to relocate the entire town of paradise. they bought out over eight hundred people and bulldozed everything they left behind—except the cemetery.3

told this way, it makes a neat ecological fable, almost biblical in its simplicity. we were given a paradise, and—by our own sinful greed—we lost it. it’s a story everybody in coal country has heard over and over. before “paradise” there was “sixteen tons”--also about muhlenberg county—and “coal miner’s daughter.” “never leave harlan alive” came out in 1997, just three years before the martin county coal slurry spill.4

it’s a good story. it’s even a true story. but it’s not the whole truth.

the town of paradise was settled by white colonists in the 1780s, as part of the wave of violent american imperialism that swept over the appalachians and stole land belonging to the Osage, Cherokee, and Shawnee, among others.

in 1838, the trail of tears passed through the neighboring county, where they made a bitter camp for the winter. there’s a plaque marking the graves of two chiefs who died there.

in 1850, a man named doctor roberts arrived in paradise, and sold the first barge of coal down the mud river to bowling green. this was before the common usage of blasting powder; that coal was dug with a sledgehammer, by candlelight, by the enslaved men that doctor roberts brought with him.

they weren’t the first or only enslaved people in the region. it was enslaved labor that dug the saltpeter out of mammoth cave for the war of 1812, and it was enslaved labor that planted, topped, cut, hung, and pressed the famous dark tobacco of greenville.5

in 1860, there were 9,000 people in muhlenberg county. almost 1,500 of them were enslaved.

because kentucky never successfully seceded—not for lack of effort—it was exempt from the 1867 reconstruction act. it therefore became a haven for confederate veterans and aggrieved white southerners. between 1910 and 1980, the Black percentage of kentucky’s population was cut in half, as people fled white violence and intolerance. today, the second-largest klan compound in the nation is in dawsons springs, kentucky—about fifty miles from paradise.

in this version of the story, there’s no nostalgia, no sense of loss. in this story, there was never any paradise to lose.

i think most of us want the truth, most of the time. we want to get to the bottom of things. we want the facts, cold and hard. we love myths, but we especially love myths debunked.

and yet, that quest—the quest for a measurable, objective, singular reality, which can be parsed by an all-seeing (and, frankly, imperial) eye—is both unhealthy to want and impossible to achieve.

history isn’t a pamphlet of facts. it’s an unwieldy combination of hearsay, rumor, folklore, half-truths, memories, desires, dreams, interviews, interpretations, re-interpretations, inventions, material evidence, lies, damn lies, and lies of omission. it’s an anthology, a palimpsest, a map drawn by committee. it’s a story, told over and over, different ways.

maybe that’s why starling house had to dabble in so many different genres. because the story of kentucky—my story, my family’s story—is a horror novel and a paperback romance, a contemporary comedy, a tragic historical, a classic coming-of-age story, a mystery, a memoir, and a pulpy gothic.

because it’s about my home, and homes are a little like history: remembered differently by each person who lived there.

of course, starling house isn’t actually a history of paradise, kentucky. i changed things, made things a little worse or a little better. i dreamed up a town that survived, rather than one that was buried. i dreamed up a girl tough enough to stay there, even as i was packing boxes and scrolling through zillow. i even gave it a happy ending, sort of. why not?

it’s my story, and i can tell it how i want to.

the last verse of “paradise” goes like this:

When I die let my ashes float down the Green River

Let my soul roll on up to the Rochester dam.

I’ll be halfway to Heaven, with Paradise waiting

Just five miles away from wherever I am.

i always liked those final lines—a bittersweet admission that paradise isn’t really a place on a map. it’s a dream, a mirage, a hope we chase after whether we find it or not.

prine died of covid in 2021; his ashes were spread—where else?—in the green river.

at the end of 2022, long after i’d finished this book, the paradise fossil plant was destroyed.6 my dad sent me a video of the demolition of the cooling towers. watching that video—the graceful, almost balletic collapse of those vast towers, the final chapter of a long, bad book—i thought: maybe i left too soon.

maybe the story is still being told, because history isn’t over. maybe it’ll even have a happy ending—it’s our story, after all, and we can tell it how we want to—or maybe a happy ending is something we chase.

maybe it’s waiting, just five miles away from wherever we are.

in the US, i mean. the UK edition won’t be out til this halloween!

there is a tiny town in butler county named eden but, with apologies to butler county, i’m not talking about that one

prine actually grew up in a chicago suburb, but his parents were from muhlenberg county. prine was in vietnam when paradise was bulldozed; his father mailed him a newspaper clipping about it. when prine got home, he played the song for his father, who got up and left the room—because he wanted to pretend he was hearing it on the radio.

which was thirty times larger than the exxon valdez spill. the utility bills in martin county still come with a notice in fine print that the drinking water is a cancer risk; massey energy paid a fine of $5,000.

my dad used to do tobacco season in allen county, in the 90s—i remember him puking for hours after cutting tobacco in the rain, because the nicotine sticks to your skin and seeps into your pores. but now that work is done by migrant workers—underpaid, unwelcomed, and unprotected. child labor laws do not apply to agriculture, in kentucky.

the plant was closed in 2019, despite opposition from the governor, the state legislature, and even the president. it was just too old, too inefficient, and too toxic.

Just this newsletter made me cry, I can only imagine what the book is going to do to me.

Thank you for sharing this truth, even if there's never *a* truth.

As someone who's been thinking & writing a lot about interpretations of southern history over the past few years, this really resonated with me—thanks for writing, and I can't wait to read the book.